Introduction

Like many other facilitators, trainers and coaches – especially those working in the DEI space – I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to build psychological safety within teams and organisations. And I’m finding it useful to think about psychological safety within a broader context of safety and wellness.

For example, our bodies are designed to react in ways that protect us against threats from predators and other aggressors. The types of threats we encounter have changed significantly over time; however, this does not mean that life is now free of stress. In fact, far from it. We face many stressful demands each day, including managing our workloads, paying bills, taking care of our families, etc. Not to mention personal traumas such as the loss of loved ones, declining health, divorce, etc.

In addition to these daily stressors and personal traumas – and often exacerbating them – is the fact that we are living in tough times. We’ve experienced a global pandemic and dramatic changes to how we conduct our daily lives; and throughout the world there are high levels of economic uncertainty, unemployment, violent crime, political and social turmoil, and natural disasters.

As a result, many of us are struggling with unprecedented levels of stress and anxiety.

What does this mean for us – as facilitators, trainers and coaches – in terms of how we support teams and organisations in the critical task of building psychological safety? First and foremost, I think we need to understand the physiology of what we are dealing with.

Understanding the Physiology of Safety

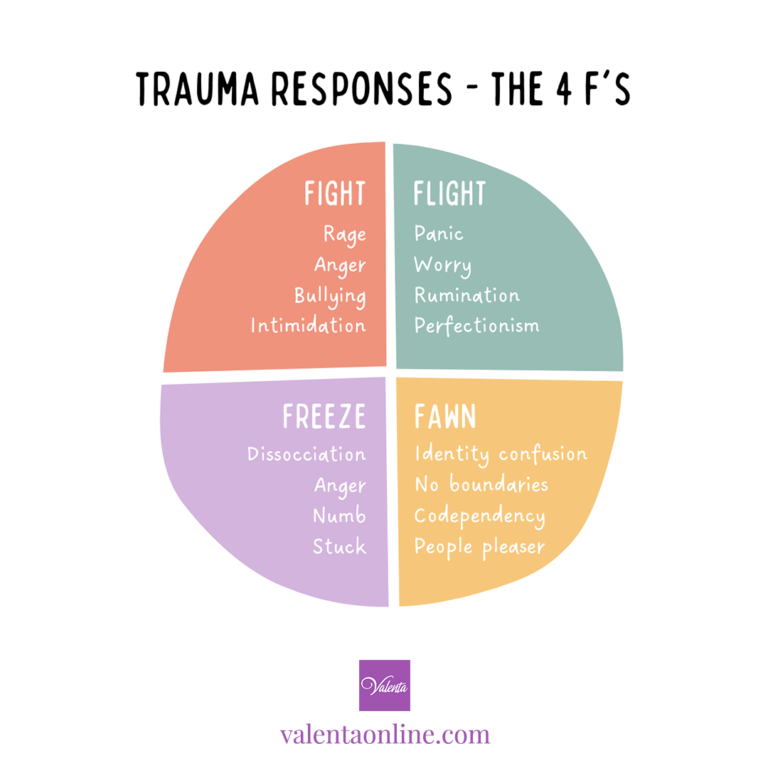

There are four commonly recognised ways in which are bodies react to a threat (real or perceived), including the stressors and traumas listed above. These are:

Fight – retaliating or confronting the threat, including physically or verbally fighting the threat, or (when unable to confront the threat) becoming hyper efficient, prepared, controlling.

Flight – running away or avoiding the threat, including by hiding out, withdrawing and disengaging.

Freeze – being physical paralyzed and/or not able to make a decision about how to respond (mind paralysis), including by ‘playing dead’, engaging in numbing behaviours, dissociating, isolating and sleeping.

Fawn (the newest accepted addition to the primary responses) – trying to avoid or minimise distress or danger by pleasing and appeasing the threat, including by doing anything that keeps the threat, or abuser, happy.

Image Credit: https://www.valentaonline.com/trauma-response-fight-flight-freeze-fawn/

What happens to our bodies in each scenario

During a fight-flight-freeze-fawn response – ‘fight-or-flight’ for short – our bodies release adrenaline and cortisol (stress hormones), which trigger a number of physiological changes:

- Heart rate. Our hearts beat faster to bring oxygen to our major muscles. During a freeze response, our heart rates might increase or decrease.

- Our breathing speeds up to deliver more oxygen to our blood. In the freeze response, we might hold our breath or restrict breathing.

- Our peripheral vision increases so we can notice our surroundings. Our pupils dilate and let in more light, which helps us see better.

- Our ears ‘perk up’ and our hearing becomes sharper.

- Blood thickens, which increases clotting factors. This prepares our bodies for injury.

- Our skin might produce more sweat or get cold. We may look pale or have goosebumps.

- Hands and feet. As blood flow increases to our major muscles, our hands and feet might get cold.

- Pain perception. Fight-or-flight temporarily reduces our perception of pain.

Once a perceived threat has passed, the adrenaline and cortisol levels drop, our heart rates and blood pressure return to typical levels and other systems go back to their regular activities.

However, when stressors are always present and we always feel under attack, that fight-or-flight reaction stays turned on.

The Effect of Long Term Stress

The long-term activation of the stress response system and too much exposure to cortisol and other stress hormones can disrupt almost all the body’s processes. This puts us at higher risk of many health problems, including anxiety, depression, digestive problems, headaches, muscle tension and pain, heart disease, heart attack, high blood pressure and stroke, sleep problems, weight gain and problems with memory and focus.

Chronic stress, therefore, can wreak havoc on our minds and bodies. This makes it very difficult to show up at work in a constructive and productive manner, let alone contribute to psychological safety within teams and organisations.

A Practical Alternative

Secondly, as facilitators, trainers and coaches, I think it means exploring other alternatives.

For example, another response to a perceived threat is to Flock; to seek out the comfort and safety of the collective.

‘Flocking’ is not a new concept. People come together in meaningful ways all the time – in both our personal and professional lives. For example, through affinity groups, coaching circles, support groups, etc.

Sometimes we come together purely for the sake of ‘flocking’ – to share, reflect on and process our thoughts and feelings in the comfort and safety of the collective (which feels especially important post-Covid).

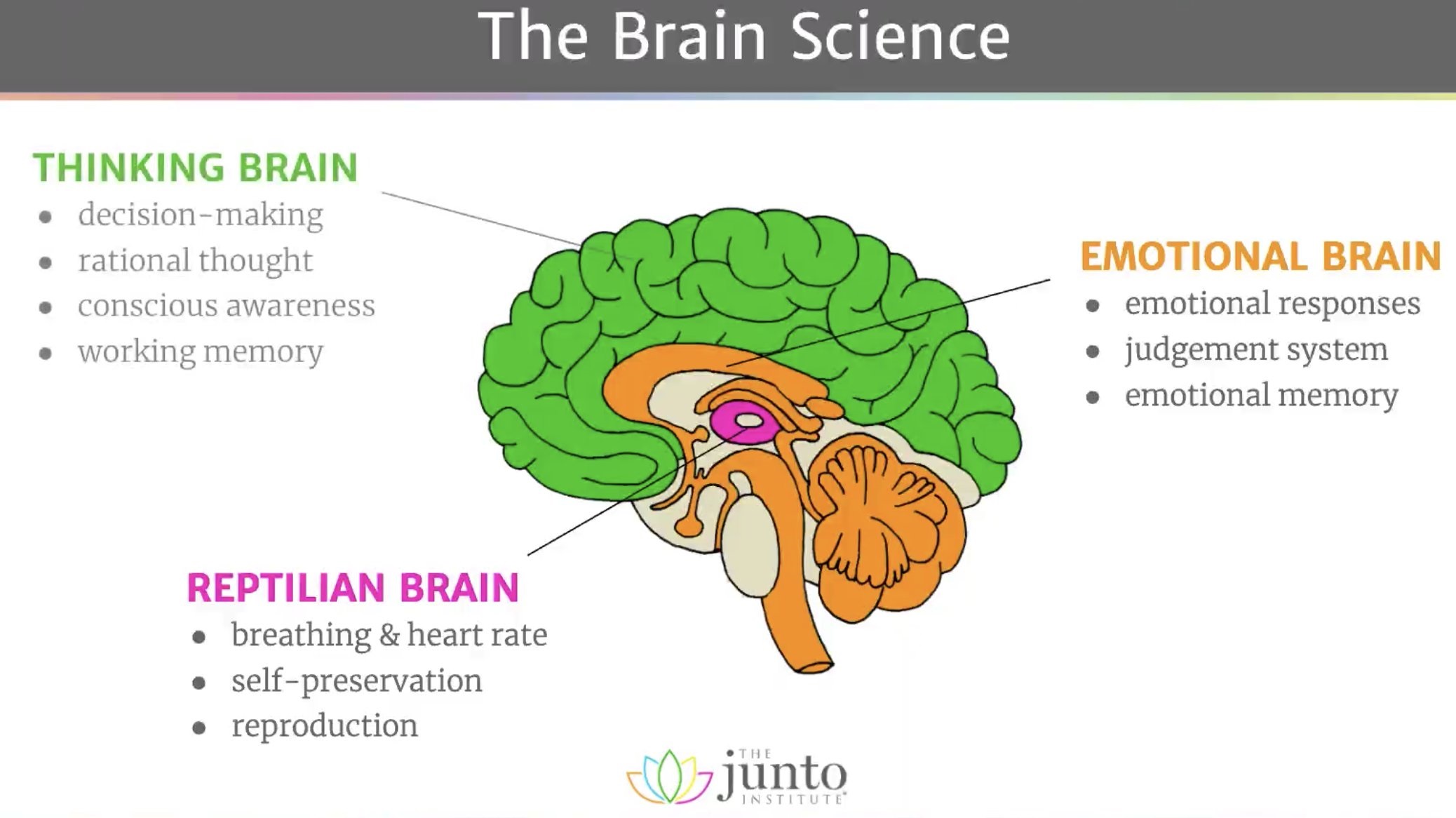

However, the value of ‘Flocking’ does not end at sharing, reflecting on and processing our feelings. When we feel an increased sense of physical and psychological safety, we are able to move from ‘survival mode’/’fight-or-flight mode’ (our emotional brains) to our ‘higher order functioning’ (our thinking brains); where, in turn, we are able to think more clearly, more creatively and make more informed decisions about how to navigate the problems and challenges we may be facing.

In the context of workplaces, the need to tap into individual and collective wisdom is critical. As is the need to promote and foster physical, mental and emotional workplace wellness.

Conclusion

Perhaps then, one of the most valuable things we could be doing right now – not only for building psychological safety, but for encouraging broader employee and organisational wellness – is supporting teams and organisations to create more spaces to ‘Flock’. More specifically, to create spaces that allow for sharing, reflecting on and processing thoughts and feelings, which, in turn allow us to move from survival mode (fight, flight, freeze or fawn) to our higher order functioning. This is both good for individual health, as we are no longer stewing in the adrenalin and cortisol and our other bodily functions are no longer in overdrive; and organisational health, as our problem-solving and decision-making skills are enhanced when we tap into our individual and collective creativity and wisdom.

In essence, it is about encouraging more spaces where synergy, innovation and solutions abound.

What are we waiting for, everyone? Let’s Flock!

Resources:

Chronic Stress Puts your Health at Risk. Mayo Clinic Staff. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20046037

Fight, Flight, Freeze: What This Response Means. Kirsten Nunez. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/fight-flight-freeze

Surviving Tough Times by Building Resilience. Robinson and Melinda Smith, M.A. https://www.helpguide.org/articles/stress/surviving-tough-times.htm

What is the Fawning Trauma Response? Katy Kandaris-Weiner, LPC. https://innerbalanceaz.com/blog/what-is-the-fawning-trauma-response

Shiftbalance is committed to psychologically safe workplaces and can assess your office through our DEI Audits. Visit our Strategy Consulting page to learn more!

Author: Sam Stern

https://www.linkedin.com/in/samantha-stern-aab44333/