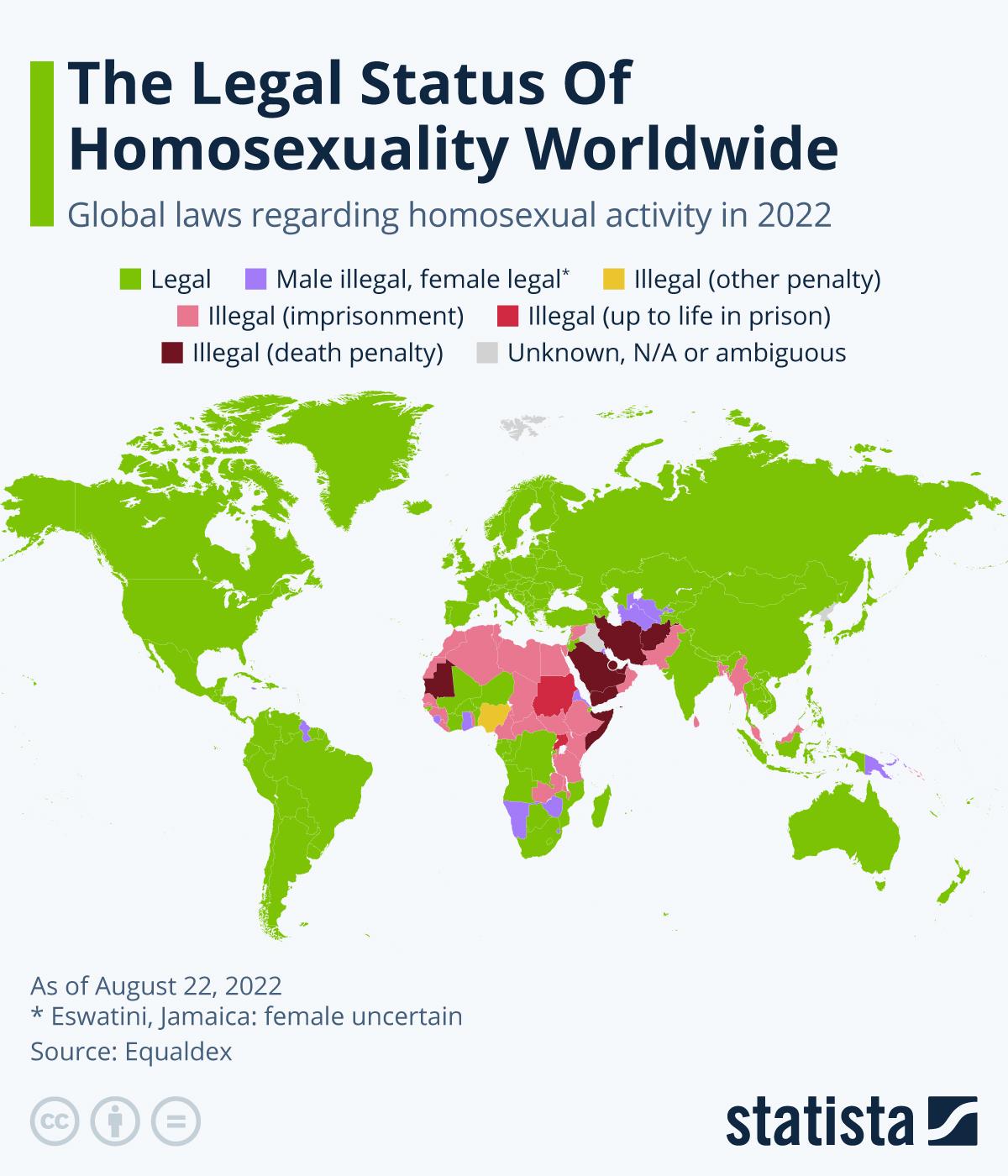

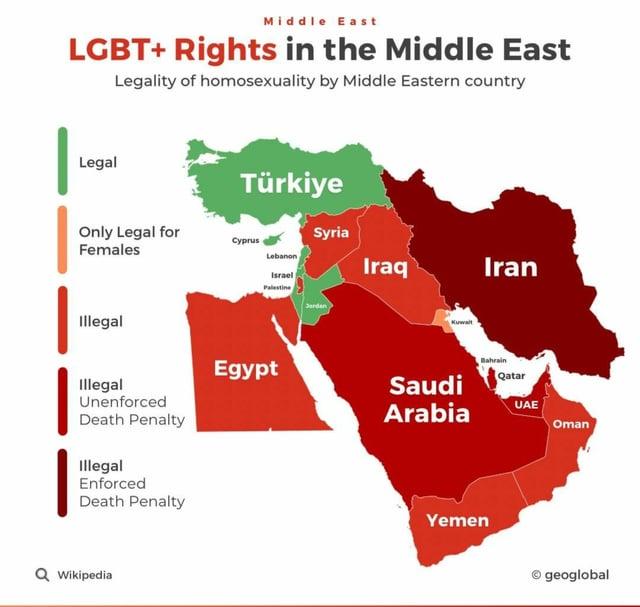

Working on LGBTQIA+ rights in Arabic-speaking countries is and has not been easy. While in most of them legislation is very clear about the criminalization of homosexuality and transgenderism, each country approaches the matter in a different way. Even in those where same-sex intercourse or cross-dressing are not explicitly prohibited, general laws on morality are often used to persecute LGBTQIA+ individuals. The penalty of consensual sexual intercourse between two adults of the same sex differs from a country to another, reaching even death penalty in Yemen, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, and Somalia. Furthermore, and even in the absence of such laws, restrictions on freedom of expression and association of LGBTQIA+ persons are sadly the norm in many countries.

For those countries that have explicit legislations against LGBTQIA+ persons, it is rare when the term “Mithlia” “مثلية” (accurate translation of the word ‘homosexuality’) is used. Some of the Arab-speaking countries use the term perversion to refer to homosexuality, while some others resort to the terms “Liwat لواط and Suhaq سحاق ” –which are in essence some derogative terms to address oneself to Gay men and Lesbian women adopted from religious books.

For those countries that have explicit legislations against LGBTQIA+ persons, it is rare when the term “Mithlia” “مثلية” (accurate translation of the word ‘homosexuality’) is used. Some of the Arab-speaking countries use the term perversion to refer to homosexuality, while some others resort to the terms “Liwat لواط and Suhaq سحاق ” –which are in essence some derogative terms to address oneself to Gay men and Lesbian women adopted from religious books.

Managing the context

Yet, one needs to navigate this complex conundrum and find some tricks to raise awareness on the matter, for which knowing the context is very important. To do that, and although in most Arab-speaking countries it is not allowed to work on LGBTQIA+ rights, we can still find some key organisations that publicly work on these issues, like some in Lebanon and Tunisia, and other key actors working underground in many other countries where the space is more limited. Therefore, while working on diversity and inclusion I always made sure to collaborate with local organizations before starting any type of work. It is very important to understand the context, and who would do it better from those who have been working on the issue?

Remember: Safety First!

While working with different organizations in Arab-speaking countries on raising awareness about LGBTQIA+ issues, I always needed to repeat to myself: “be cautious”. State interference in the region is very present. Do not be surprised if you are conducting a training and someone is listening behind the walls. Yes, it is not a joke, it happened to me, and it happens to many of us.

Thus, what to do in this case? “Be Prepared”. For example, I never mention any word related to LGBTQIA+ in my training agendas or invitations. Instead, I tend to “be more general” about the terms I use (e.g. reproductive or personal health instead of sexual health, rights of minorities instead of LGBTQIA+ rights…). During my sessions, I always bring the discussion to a main idea: we need to provide services and equity to everyone regardless of their identity (so that I do not sound as if I am promoting LGBTQIA+ rights per se).

I cannot recall how many times I heard that homosexuality is a western import -and I am sure anyone training on LGBTQIA+ matters in Arab-speaking countries has witnessed that too. What can we do in these situations? I always had “prepared facts in my pocket.” For example, having knowledge on the presence of homosexuality in Arabic literature, which is known in the pieces by Abou Nawas and Bashar Bin Burd, among others. We can reinforce these ideas as well by mentioning the date when homosexuality ceased from being considered a disorder by the World Health Organization, if someone in the audience brings that association of ideas.

Do not be driven by assumptions and be mindful of your own biases

All along my experience, the main lesson learned from working on diversity and inclusion is: “Do not be driven by assumptions and be mindful of your own biases”. We all come with a sociocultural baggage and, as a trainer, “I am not here to change your beliefs.” Having those premises in mind always help create a sense of a safe space in the room and have a smooth discussion regarding a topic that still creates many resistances. More specifically, people often rely on religion to defend their opinions, for which it is very important that we do not give our opinion about any religion or try to state our own interpretations. People are free to believe in any religion they want, but they cannot impose their beliefs on others either. In these situations, we need to remind people that working in a human rights organization obliges us to treat everyone equally regardless of their background, going back to the basics: Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

To sum up and although change takes long (even generations), it is fascinating and fulfilling to be part of any action and movement towards justice, equity and, in specific contexts like Arab Speaking countries, ultimately, saving lives.

Author: Mahdy Charafeddin

Shiftbalance provides sensitive diversity and inclusion trainings in a variety of contexts around the world, as well as unconscious bias training. We have online courses on allyship and other resources to become a better ally. To see more about our experience, check our Learning & Development page.